22 de septiembre 2020

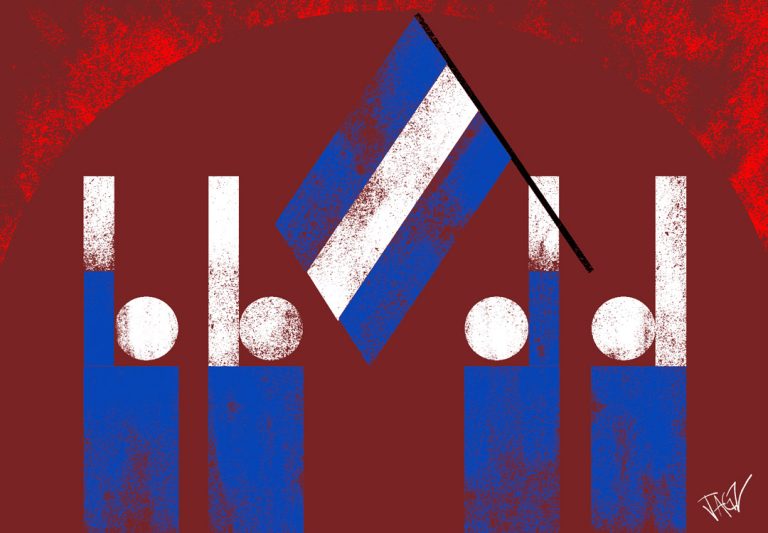

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Without jobs, “with a record,” persecuted or in exile, they try to rebuild their lives despite a police state, the pandemic and the economic situation

Without jobs

The lives of the political prisoners of the Ortega-Murillo regime have changed forever. They not only lost their freedom but also their means of subsistence: businesses, enterprises, employment, harvests.

Upon leaving prison, they found their homes and businesses looted and accumulated debts. They faced the difficulties of carrying the burden of an opponent of the regime, in Nicaragua, during an economic depression. Then, to top it off, came the health crisis due to Covid-19. Everyone’s plans, however, remain the same: resist and hold on.

Kisha Lopez was in a men’s prison for more than 10 months. They accused her of financing the roadblocks in Diriamba. Photo: Claudia Tijerino / Confidencial

Kisha Lopez couldn’t bear the tears upon returning home after eleven months of imprisonment to find her house and business destroyed. “I didn’t have a single Cordoba in my wallet,” she recalls. Of stock from her electrical appliances business, jewelry, and used clothing there was only broken glass. A list of debtors remained from personal loans she made, which included Ortega supporters, who now refused to pay her.

This trans woman, a native of the department of Carazo, was sentenced by the regime for allegedly financing terrorism. Everything she had built with years of work was destroyed or stolen during the raid by police and paramilitaries.

“I wasn’t wealthy, I am simply a person that was making a living,” she says. On July 9, 2018, when she was arrested, the police confiscated 36,600 dollars, 55,600 cordobas, jewelry, a motorcycle, and all the electrical appliances of her business. On that same day, all the people that owed her money also “disappeared.” Most of them are state workers, who now “play being angry,” she narrates.

Collecting the debts became “a nightmare” for Kisha. A high-level official from the Ministry of Education (MINED) “told me that if I continue trying to collect his debt there, he would accuse me of death threats. So, because I feared being incarcerated again, I left it as it is,” she recalls.

Of the more than 30,000 dollars she had placed in loans, Kisha only recovered 3,000 dollars. She had to sell the car in her possession to repair her house and restart her used clothes business. The decision she made after crying when she returned home she wasn’t going to show any sign of weakness. “This is my life, a now I have to go forward,” she said.

Yubrank Suazo dances folklore in the city of Masaya, the day of his release. Photo: Carlos Herrera | Confidencial

At the Suazo family’s hammock workshop in Masaya, you feel the enthusiasm and a desire to work. The hands of each artisan weave colored threads. Also, the dreams of a family that yearns to reposition itself among the largest exporters of hammocks in Nicaragua. The quality of the products is indisputable, but tourists don’t dare visit the place as they did two years ago. The workshop is also the home of former political prisoner Yubrank Suazo. He is trying to recover the life, the home, and the business he lost during the April Rebellion.

Yubrank was arrested on September 10, 2018, accused of “terrorism”. He was released in June 2019, under the Amnesty Law, classified as self-amnesty for the Ortega regime.

Economic losses for the family’s property, household items, and business raw materials exceed 50,000. Yubrank assures, however, that his family keeps intact “the spirit of improvement.” The Suazo’s have returned to making hammocks, flower arrangements, and bags. “We cannot remain with the mentality of always making ourselves the victims. That doesn’t help at all for emotional, or economic, growth,” says Yubrank.

Starting from scratch and with the stigma of being a former political prisoner is hard, but not impossible, he says. For Yubrank and his family, the most complicated part has been the constant besiegement. “Tourists are afraid to risk coming (to buy) at the house. They fear being linked to purely political actions.” Updating the business information at the tax office (DGI) to process export permits, was also complicated. “They asked us for information they already had in the system and we didn’t, because our house burned,” he recalls.

Since being released from prison on May 20, 2019, former political prisoner Kenia Gutierrez has changed her home 13 times. The besiegement against her and her relatives is the main obstacle for her to resume her life and her business. To try and get back where it was before the April 2018 rebellion. The persecution forced her to leave the municipality of El Viejo, in Chinandega, and move to Managua. However, she has not been able to establish herself in the capital either.

Every time Kenia stays somewhere, the police arrive to besiege. The constant presence of those in uniform has caused the property owners to throw her out on the street. “You can’t stay here,” “we don’t want problems,” she has been told on multiple occasions. One time they gave her “one hour to vacate the apartment.” “I just didn’t have anywhere to go, or how to do it. It has been quite difficult,” she laments.

Economic losses for the family’s property, household items, and business raw materials exceed 50,000. Yubrank assures, however, that his family keeps intact “the spirit of improvement.” The Suazo’s have returned to making hammocks, flower arrangements, and bags. “We cannot remain with the mentality of always making ourselves the victims. That doesn’t help at all for emotional, or economic, growth,” says Yubrank.

Starting from scratch and with the stigma of being a former political prisoner is hard, but not impossible, he says. For Yubrank and his family, the most complicated part has been the constant besiegement. “Tourists are afraid to risk coming (to buy) at the house. They fear being linked to purely political actions.” Updating the business information at the tax office (DGI) to process export permits, was also complicated. “They asked us for information they already had in the system and we didn’t, because our house burned,” he recalls.

Cristhian Fajardo with his wife, Maria Adilia Peralta. Photo: Carlos Herrera / Archive Confidencial

Before ending up in jail for protesting against the Ortega regime, Cristhian Fajardo could take his Harley Davidson motorcycle and go on a trip from Panama to Mexico. He was just married and owned a hotel in the city of Masaya, which was burned on June 20, 2018. A year later, when he was released “practically bankrupt” and full of debts.

Losses from the fire were around 300,000 dollars, between the building and everything looted or consumed by the flames. “It was my only means of income,” recalls Cristhian. Today he’s in exile with his wife Maria Adilia Peralta, also a former political prisoner of the regime.

After prison, Cristhian only had “debts to meet”. He assures that on several occasions “they tried to buy him,” but he remains firm in his convictions. “I didn’t get into this struggle looking for a bone. I had my financial life resolved,” he adds.

For Cristhian, traveling was his passion. He had visited Europe and the United States on multiple occasions, but “after getting out of prison, the only trip I had was to exile,” he laments. Without resources, he and his wife sleep in the living room of an apartment rented by his mother, a US citizen.

Exile “is not easy,” he says. Presently he divides his time between searching for the means to survive and his political work. There are times when he feels discouraged, then he disconnects from social networks. But “when I re-energize, I continue in my political work,” he says.

Cristhian ponders on his current condition. “No matter how bad, I cannot be worse off than at Gallery 300, in the La Modelo prison. They were slowly killing me there.”

Former political prisoner Ana Cecilia Hooker sells costume jewelry in churches, at important meetings, or at press conferences. The blue and white bracelets that she and other former political prisoners sold when they were released from prison, became trendy among Nicaraguans opponents of the Government.

Before the April Rebellion, Ana Cecilia was a university professor and human rights promoter. In her spare time, she ran a small handicraft shop in Somoto. That all ended with her arrest on November 19, 2018.

Since the anti-government protests began, Ana’s business took a nosedive. Supporters of the regime began to boycott her work. First, they ran off customers who came to the store. Then they posted her photograph in the Sandinista Front office in Madriz. “They wouldn’t let me work on my own. By September 2018 I could no longer leave my house. I couldn’t go buy materials, I had my showcases broken until they kidnapped me.”

When released in February 2019, she no longer had a business, or savings and her family was financially exhausted. Before being incarcerated, she was “the breadwinner” and couldn’t give up. She went back to making costume jewelry, “wherever I go, I take my merchandise.” Sometimes people congratulate her, others criticize her. “It’s a difficult situation, but I have a daughter and our needs, and if I don’t work, we don’t eat.”

The market for costume jewelry isn’t the best as Nicaragua faces an economic depression. Ana can’t even sell at a specific point because she carries the stigma of being a former political prisoner. Nor does she sell on Facebook for fear of having to meet strangers. Despite all the vicissitudes, she assures, “I believe in my project, it is something that I had before. I don’t want to give it up.”

On some occasions, when the former political prisoner Max Cruz tries to leave Ometepe Island, where he is from, the ferry administrators don’t let him board. He returns to his farm. He walks with difficulty, because the fracture caused during his arrest, in October 2018, was not well healed during the six months that he remained in prison. His constraints to move around, however, have not prevented him from resuming his life along with his three children. He remembers finding them “like lost chicks” on March 15, 2019, when he was released from prison.

Max’s farm looks abandoned. “One of my brothers committed suicide or was killed, only God knows what happened to him. My other brother went (into exile) to Costa Rica,” during the days of the Clean Up Operation, in 2018. With the help of some friends, Max managed to “plant some beans to eat. They are not so good, but it is something. We also grow a product called turmeric and other vegetables. But now we have another problem, we have some production, but we don’t have a market,” he laments.

The economic losses on the farm are difficult to calculate, they haven’t been able to cultivate most of the land. And the two houses of the property have the roof and walls riddled with bullet holes. Shots from when the Police arrested Max and his wife Marbi Salazar. In the small grocery store they had, only empty shelves and old refrigerators remain.

Max has trouble standing or sitting for long periods of time. In jail, he acquired a bacterium in his broken leg, and he has not completely healed. Occasionally, he travels to Managua to receive medical attention. However, there are times he has no money “not even for the bus fare.”

After prison, life is never the same again, for more than 850 political prisoners of the Ortega regime. After suffering torture in the dictatorship’s prisons, they still face police besiegement. For them, the barriers go beyond the prison, they endure persecution and permanent harassment.

The confinement left them practically on the street, their families indebted, and job opportunities reduced even more. Now they are trying to bounce back despite the difficulties, while the majority continue to make opposition.

Faced with obstacles to finding a job or resume their studies, several former political prisoners began their own businesses. In Matagalpa, university students and former political prisoners Dilon Zeledon and Roberto Buschting started a coffee business called Tattoo Café. They hope to grow and employ other former political prisoners in similar difficulties.

Victoria Obando, a trans university student, and former political prisoner started a small café. It’s called “Cravings, coffee, and desserts,” located in the Los Robles neighborhood in Managua.

Likewise, former political prisoner Ulises Rivas, from Santo Domingo, Chontales has a hamburger business.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996.

PUBLICIDAD 3D