25 de enero 2023

Six Years With April in Tow: Life Under Nicaragua's New 'Normal'

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

A look at the past to recover historical memory and keep hope alive

A look at the past to recover historical memory and keep hope alive

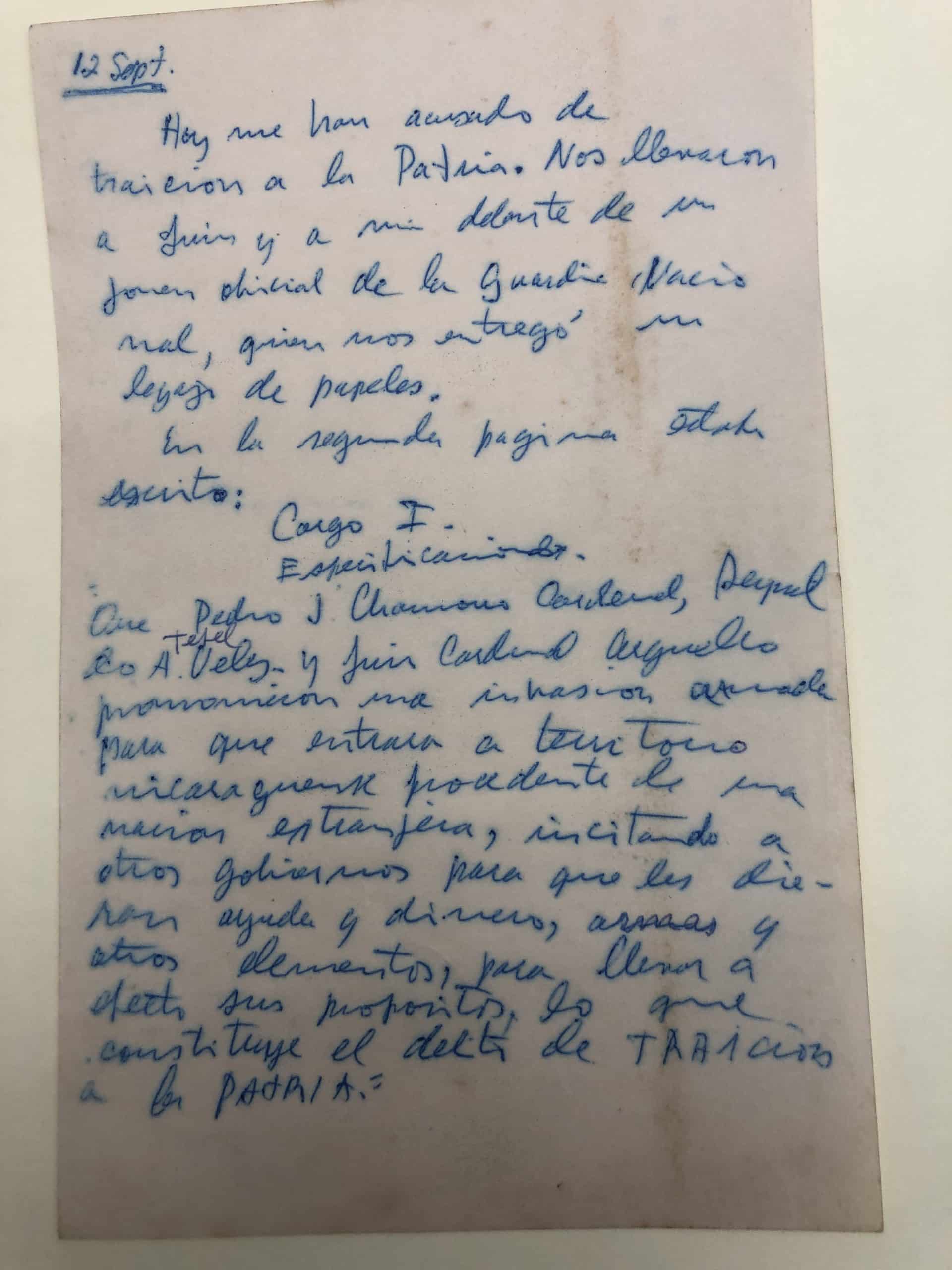

"Protest. We Nicaraguan patriots who have fought since we were children to establish a true democracy in our homeland, and who for that reason have been condemned by a military tribunal and cataloged with the infamous epithet of 'traitors to the country', have decided to manifest our protest by declaring ourselves on hunger strike."

So begins a letter signed by my father, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, Reinaldo Antonio Téfel, and Ronald Abaunza, political prisoners held in the cells of the Loma de Tiscapa prison during the Somoza dictatorship, and written on an unspecified date in the last quarter of 1959. The manuscript is one of the hundreds of historical documents that I was able to read at the Latin American Library of Tulane University, a few hours before the inauguration, on November 8, 2022 ,of the "Chamorro Barrios Archive", donated to that prestigious university by my family.

The archive contains documents spanning from the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century. They come from four documentary sources: the collection of my grandfather Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya, professional historian and journalist, primarily covering 1810 to 1948; the manuscripts of my father, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, journalist and anti-Somocista fighter, covering 1957-1961, and some from the 1970s; the papers of my mother Violeta Barrios de Chamorro on La Prensa in the 1980s, her election campaign in 1989-1990, and her state speeches as president between 1990 and 1997; and the papers of my brother-in-law, Antonio Lacayo Oyanguren, who played a key role in the democratic transition between 1989 and 1997 as my mother's campaign manager and Minister of the Presidency during her government.

It is a collection of living documents that illuminate the present, such as the one that describes the hunger strike of the prisoners in 1959. Sixty-three years later, in the El Chipote jail in 2022, political prisoners Dora María Téllez, Miguel Mora, Miguel Mendoza, Irving Larios, and Róger Reyes, all convicted of "conspiracy against national sovereignty", carry out hunger strikes to end solitary confinement, and demand the right to reading and writing materials for all political prisoners, and to be able to communicate with their young children.

This historical archive allows us to explore our roots, draw lessons from the past, and reflect on why Nicaragua's history repeats itself in an increasingly tragic way, with family dictatorships, political prisoners, and crimes left in impunity. But it's also an archive that brings together a legacy of democratic values: my father preached by example and my mother by her commitment to a government based on freedom. The relay race of historical memory offers us great lessons of hope for the reconstruction of Nicaragua.

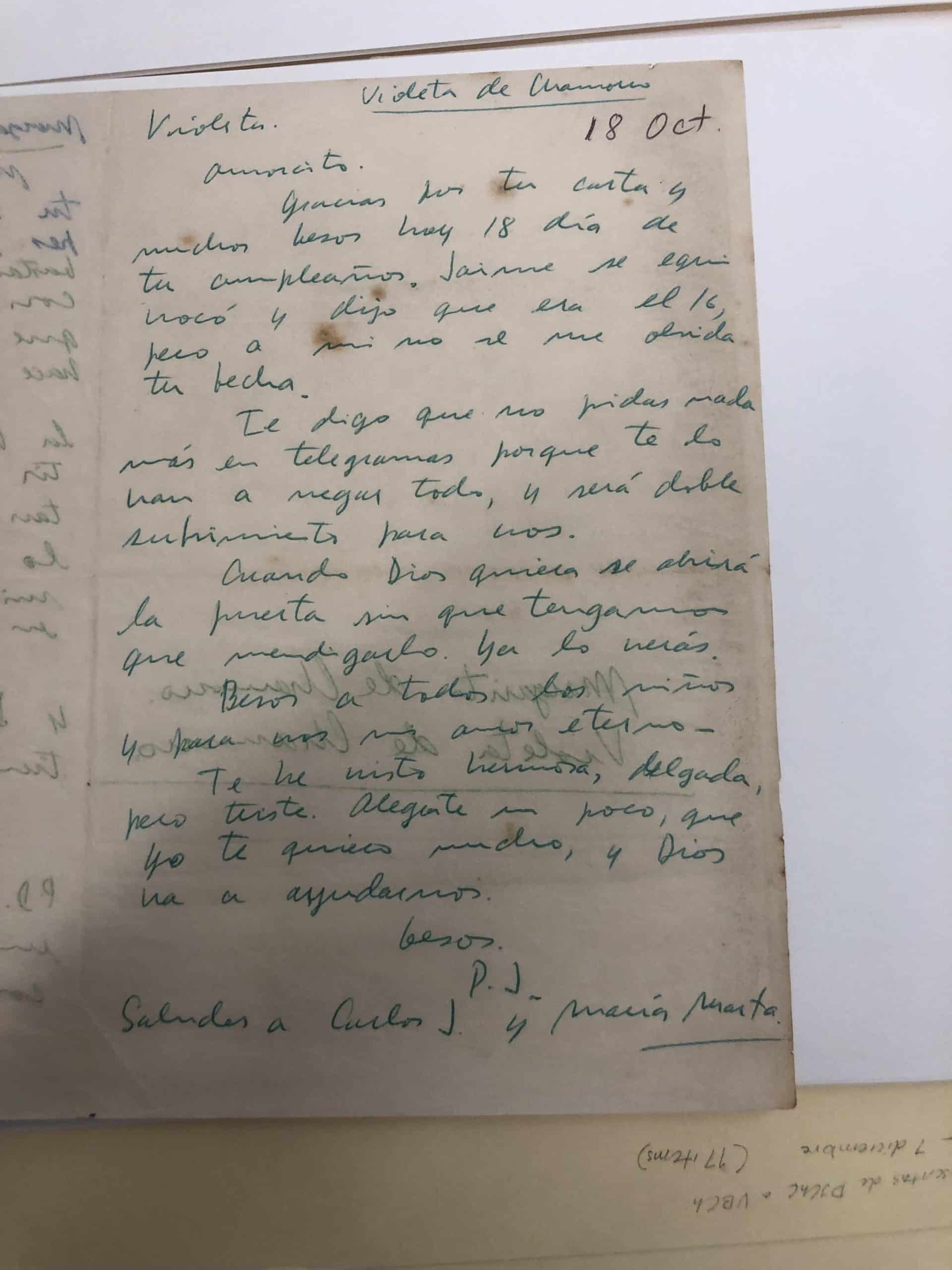

Among all the documents I read in just five hours –when I needed at least five days to begin to know the scope of the archive–, I was especially moved by the papers written by my father when he was in exile in Costa Rica, between 1957 and 1959, and the exchange of letters he had with my mother, during his third imprisonment under the Somoza dictatorship, between 1959 and 1961. Letters, notes, and messages written with urgency reveal a true love story, which is also a story of pain, resilience, patriotism, and hope.

Letter from PJCH to his wife Violeta Barrios de Chamorro on her birthday: October 18, 1959.

There is, for example, the complete manuscript of Diary of a Prisoner, published in 1962, and written by my father during three or four months, first in the cells of the Third Company and then in the cells of the First Presidential Battalion in the Loma de Tiscapa prison. It was a handwritten manuscript on small pieces of paper that he would later send to my mother through lawyers or visitors to be transcribed.

Diary of a Prisoner manuscript

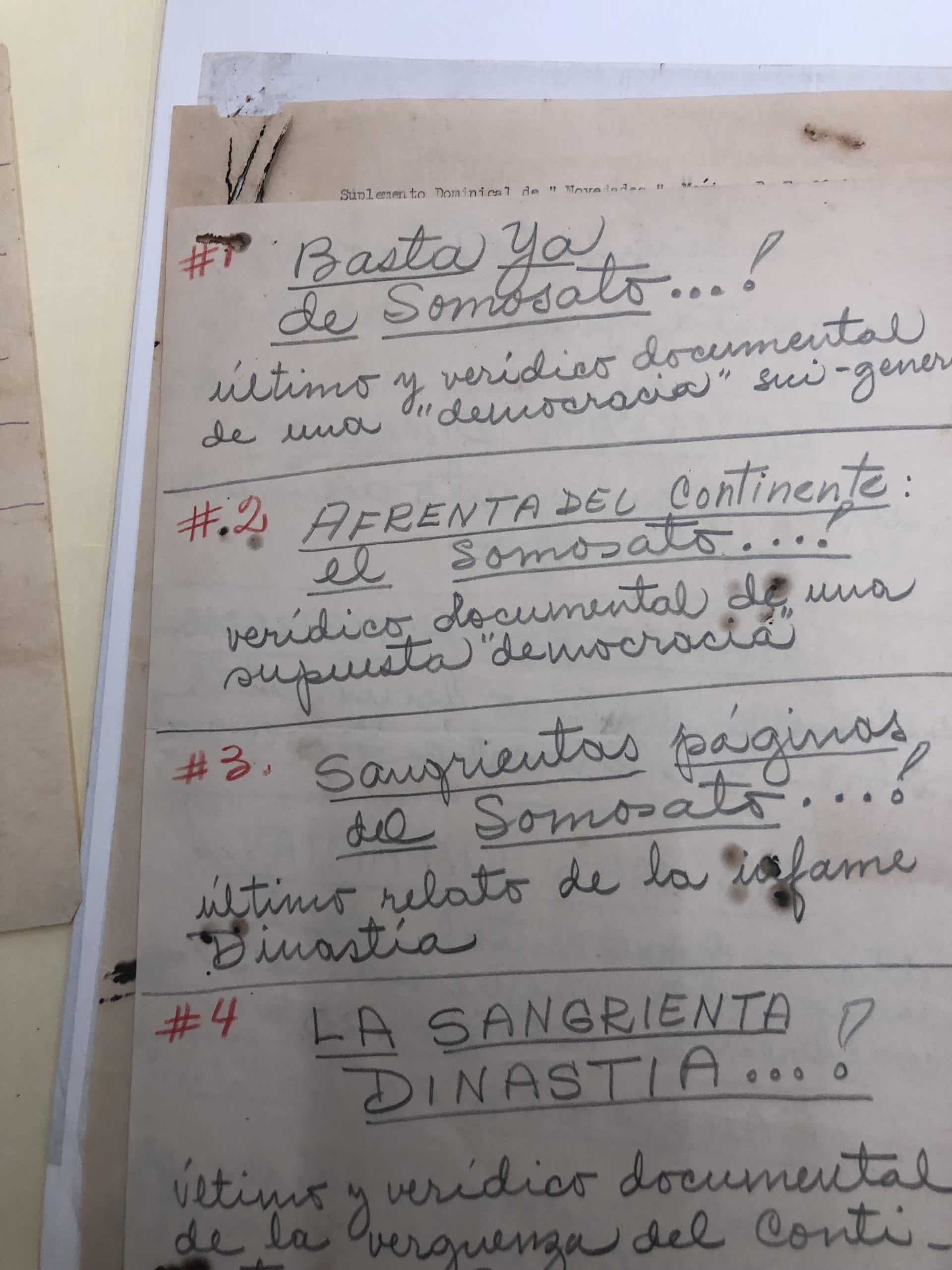

There is also the epistolary account of the publication of the first edition of his book Bloody Lineage: The Somozas, which contains the testimony of the torture he and his comrades endured at the dawn of the dynastic dictatorship after the April rebellion in 1954 and the death of Somoza Garcia in 1956. It was first published in Mexico in 1957, under the editorial care of the poet Ernesto Mejia Sánchez, whom my father calls "Melqui" in his correspondence.

The collection occupies 46 linear feet of physical space on the library shelves, and brings together a total of 10,450 items of manuscript material –documents, correspondence, publications, newspaper clippings, and maps– in addition to 6,365 photographs, for a total of 16,815 items.

Proposals for the title of the book Bloody Lineage

The materials are all registered in a detailed catalog, the work of Dr. Hortensia Calvo, director of the Latin American Library, and her extraordinary team of documentalists. From this moment on, it is open to the public, visitors, students and researchers to access the physical documents that are not yet digitized.

The archive is organized into four series, corresponding to Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, and Antonio Lacayo Oyanguren. Each series is organized into subseries based on the content of the personal documents of each of the authors. The subseries include: biographical material, correspondence, personal and professional writings; research and working papers; collections of printed materials; photographs and newspaper clippings.

There are two special subseries in the collection. The first is an extensive archive of the colonial era and 19th century documents, compiled by Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya. The second is a collection of covers and mockups of pages of the newspaper La Prensa that were censored in the 1970s and 1980s.

The donation of these papers to Tulane University is a project that was started in 2020 by my sister Cristiana Chamorro, in her role as custodian of this document collection.

Cristiana could not attend the inauguration of the archive because she has been a political prisoner in Nicaragua for 600 days, as has my brother Pedro Joaquín (577 days) and my first cousins Juan Sebastián Chamorro (594 days) and Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro (528 days).

They are prisoners of conscience, and together with some 230 other political prisoners, have been condemned in mock trials to sentences ranging from eight to thirteen years in prison for the alleged crimes of "conspiracy against national sovereignty", "money laundering" and "propagation of fake news". All of them are innocent, and their only crime has been to demand free elections as an essential element of the aspirations for democracy and justice of a people who do not wish to live in a dictatorship.

This is the text that Cristiana wrote in early 2021, when she was still free, to thank Tulane University for receiving and safely preserving this donation of documents that is now available to the public.

Cristiana Chamorro Barrios.

History is not written with propaganda speeches but rather with evidence gathered in the archives of its protagonists. These documents should be put at the service of new generations so they can learn from history’s lessons and mistakes.

In honor of the sacrifice of my parents, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal and Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, in grateful acknowledgment of their lives and to honor their exemplary service and love for country, the Chamorro Barrios family decided to donate all of their personal papers to Tulane University and its Latin American Library.

We did this to share their legacy with new generations and, in that way, to pass down their human, historical and political legacy in their struggle for democracy, peace, economic and social development of Nicaragua.

Our objective is to contribute to the recovery and preservation of Nicaragua’s historical memory. For academic researchers, the papers of Pedro and Violeta Chamorro offer a window directly into the key issues of the country’s development in the 20th century. At the same time, their histories help construct historical, political and cultural references that may serve civil society in Nicaragua and its younger generations who are constructing the future of the country right now.

Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, a journalist assassinated in January 1978, triumphed posthumously with the Revolution that brought down the Somoza family regime in 1979, and later with the presidency of his widow Violeta Chamorro (1990-1997).

The story of my mother, Violeta, is a continuation of my father’s long decades of struggle for democracy in Nicaragua. She picked up his banner to reconstruct the country following a right-wing dictatorship and later, when the Somoza regime was replaced by a left wing dictatorship, Violeta kept alive the struggle for public freedoms.

With a message of love and national reconciliation, in 1990, she put an end to a devastating civil war and carried out a triple democratic transition within the history of the country: from war to peace, from totalitarianism to democracy, and from a static economy to a free market.

At present, in 2021, Nicaragua again lives a moment of polarization under increasing tyranny. Within that context, my parents’ twin stories remind us of Pedro Joaquin’s mantra: “Nicaragua will once again become a Republic.”

Each one of the documents in my parents’ personal archive donated to Tulane are a reminder that democracy and fundamental human rights are not abstract concepts but realities that need constant human effort and the active engagement of men and women to consolidate them when they exist or to institute them when they don’t have the joy of possessing them, as has been the case in Nicaragua in some periods of its history.

The Chamorro Barrios family chose Tulane and the Latin American Library for many reasons. One of the main ones are its longstanding focus on Central America since its founding.

Tulane already housed several collections of unique historical material from Nicaragua. Among the most important, for example, are papers relating to two presidents, Joaquín Zavala Solís and Adolfo Díaz, and some correspondence of General Emiliano Chamorro, a member of our family.

We wanted to be part of these and other collections that help understand other periods of Nicaraguan history, such as a wonderful photographic album of photographs of U.S. soldiers in Nicaragua during the North American occupation at the beginning of the 20th century. Also, the Latin American Library has a collection of papers from Callender Fayssoux, William Walker’s aide-de-camp in Nicaragua.

Another motivation for the Chamorro Barrios family to make this donation is that we know that Tulane has worked for many years with the Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica at the University of Central America [in Managua] on a project to digitally unite these presidential collections that reside physically in the two institutions.

We also did it because at Tulane all of the Latin American Books and documents are housed in one single administrative unit at The Latin American Library. This is important for several reasons, including the fact that it’s a library that occupies a dedicated physical space with a permanent cycle of exhibitions and public events relating to the collections.

We know that library collections do not mean much if they are not made available to the public. But above all it is crucial to have a permanent staff of specialists who can speak the language, know the culture, and determine priorities of processing.

Another motivation we had is that Tulane receives a steady stream of researchers from all over the world who come to consult its collections. Most especally, we appreciate the scholarships afforded by the gift of historian Richard Greenleaf to support Latin American scholars specifically to use the library.

For these and many other reasons that I am sure I am leaving out, we consider The Latin American Library at Tulane University the best place to preserve and make accesible to the public the documentary legacy of Joaquín and Violeta Barrios de Chamorro and, in general, of those who have been important actors in the modern history of Nicaragua.

The Chamorro Barrios family is grateful to Tulane for serving as the guardian of this historical collection. Thank you.

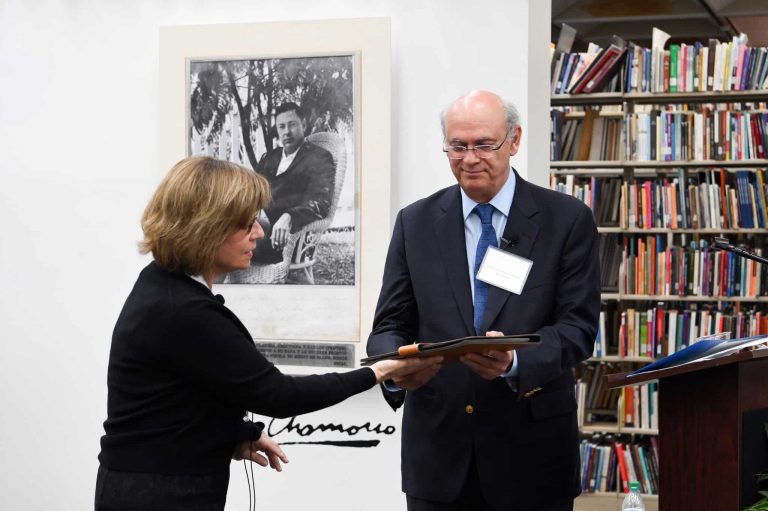

Inauguration of the “Archivo Chamorro Barrios” at the The Latin American Library at Tulane University.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D