16 de octubre 2017

The Return of the Military

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The solution isn’t to be found in the US Congress, but in the Managua neighborhood of El Carmen, where the President and Vice President live.

Even before it becomes law, the passage of the “Nica Act” in the US Congress with its threat of economic sanctions against Nicaragua is already having deep repercussions in our country. Certainly, the large business sector is concerned about the negative impact it might have on the investment climate, but the principal change in the political dynamic is by diverting attention away from the actual roots of our national problem and focusing it on the United States.

While in Washington, some members of Congress attempt to revive the failed scheme of micromanaging our national policy to fit their interests, in Nicaragua some of the leadership erroneously seeks solutions through outside pressures exerted from the US capital. They forget, or simply don’t want to face the fact, that the Nicaraguan problem – Ortega’s authoritarianism, the democratic collapse and the regime’s galloping corruption – is rooted in the offices of the Party-State-Family system in the El Carmen suburb, and not outside the country.

During the 1992 US election campaign, James Carville, Bill Clinton’s political strategist, coined the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid!” Using this phrase, the campaign centered all the Clinton firepower around a single theme to beat George Bush. In Nicaragua, if they truthfully want to promote a change, the leaders of COSEP [Superior Council of Private Enterprise] and AmCham [American Chamber of Commerce], together with the opposition parties and civil society, should be paraphrasing this slogan with a single phrase on their strategic planning boards: “The problem’s in El Carmen, Stupid.”

It’s understandable that the large executives have mounted their own embassy in Washington, since they mistrust the effectiveness of the Government’s external policies. However, until they decide to put limits on Ortega’s authoritarian power in Managua, their initiative of contracting the Carmen Group to lobby in Washington will have little credibility and is destined to fail. Because in the final reckoning, everyone knows – in Managua as well as in Washington – that the corporate-friendly authoritarian regime, the badly named “COSEP model”’, offers Ortega legitimacy to govern with no political opposition, no democracy and no transparency. As such, it forms an integral part of the knot of the problem, a knot that urgently needs to be untied via a political solution. As a result, all roads of the Carmen Group also lead to El Carmen.

In the corridors of the US Senate, Nicaragua isn’t news. The scarce interest in Latin America is dominated by the crisis of Maduro’s regime in Venezuela, Trump’s attempt to satisfy the Miami Cuban lobby and distance himself from Obama’s legacy in Cuba, and the prospect of revisions in the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico.

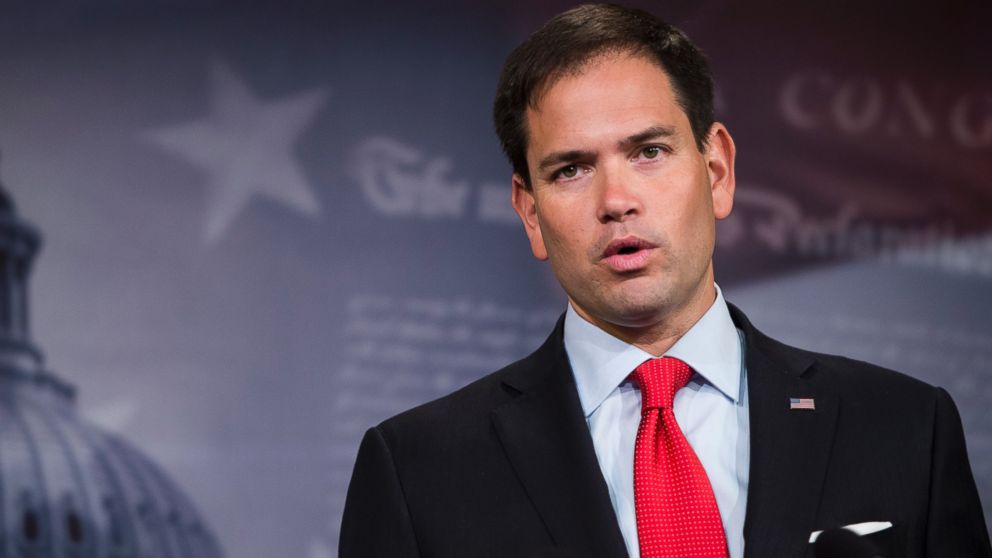

Marcos Rubio.

It was Ortega and not Senator Marco Rubio that put Nicaragua on the agenda last year, when he outlawed the opposition and closed off the political openings before the presidential elections. And in the wake of the threatened “Nica Act”, negotiations between Ortega and OAS Secretary General Almagro emerged, providential for both: the comandante obtained a “fresh start with a clean slate” for his authoritarian swing, and the OAS secretary general gained the promise of allowing the 2021 elections to be monitored. Disregarding Nicaragua’s flagrant violations of the Democratic Charter in Nicaragua, Almagro inaugurated his own policy of “a stick for Maduro and a carrot for Ortega” all within a landscape fertilized by the vacuum in the Nicaraguan opposition and the lack of guarantees of any deep electoral reforms.

Now Wilfredo Penco – who up until a short time ago partnered with magistrate Roberto Rivas to put the seal of approval on the frauds of the Supreme Electoral Council and the FSLN in 2008, 2011, and 2016 – is the new head of the OAS mission in Managua charged with issuing a report on the November 5th municipal elections. The question is whether Almagro’s delegate will read a report that is a mere formality regarding what occurs November 5th, an event that the Carter Center’s “Friends of the OAS Democratic Charter” rightly characterizes as, “a hand that’s already been played”, or if it will focus on the structural problem of party loyalty, opaqueness and lack of competition in the electoral system, as the observation missions led by Dante Caputo and Luis Yanez did in their time, when they were sent by the OAS and the European Union respectively during the unconstitutional reelection of Ortega in 2011.

This is the question that they’re waiting to clear up in the Senate, in order to decide on the destiny of the “Nica Act”; on it hangs the question of whether the draft will sleep the sleep of the just or whether it will enter into a process of negotiation and modification of the draft bill approved in the lower chamber. In the short run, though, Ortega has emerged as the net winner of the “Nica Act”: not only does it divert attention away from the national problem and onto “external factors”, but also the comandante now has an interventionist enemy in Washington. This creates an opportune pretext for criminalizing the opposition each time they question the outrages of his authoritarian regime bound up in corruption.

Nevertheless, at the margin of what the OAS report may establish or omit, there are at least two factors that could put Ortega’s regime in the Congressional and White House spotlights with devastating impact. One involves Ortega’s ties with Nicolas Maduro, his militant solidarity with Maduro’s corrupt and repressive regime (now termed a narco-dictatorship) and the client-state relationship of his government and private businesses through Albanisa with PDVSA, now subject to economic sanctions of irreversible reach and repercussions.

The second factor could be Ortega’s relationship with Putin’s Russia – recently sanctioned by the Senate against the will of President Trump himself – a toxic relation from the point of view of national security. This for the US Senate has more relevance than any other consideration of democracy, elections and the supposed seal of approval that the OAS might give to Ortega. Just as in Managua policy is made and decided exclusively in El Carmen, ironically in Washington the principal promotor of the “Nica Act” in the Senate and the decisive actor in having the White House apply direct sanctions against the regime and its intimates is also the president himself, Daniel Ortega, and his vice president Rosario Murillo.

-¿Could I speak with Mr. Cruz, please?

In the White House, the most influential person on Latin America these days has the last name of Cruz. It’s not Arturo, the competent and well-informed Nicaraguan ex-ambassador in Washington, nor is it the vitriolic ultra-right senator Ted Cruz. Rather, it’s Juan Cruz, a Puerto Rican, formerly head of the CIA office in Columbia and the agency’s ex-director for Latin America. (Don’t bother looking for Juan Cruz in Google, because there are still no photos available of this figure, whose career has been lived out in the shadows). His official position is chief advisor to the president in areas of National Security for the Western Hemisphere.

“Joe Cruz is professional, intelligent, pragmatic; he knows Latin America well, he has contacts in the region, but he’s anguished by the weight of the crisis in Venezuela,” an expert in security explained to me. The dominant version among those who know Trump’s opaque inner circle is that Cruz is in charge of the crisis in Venezuela, and has no energy or resources to concern himself with other topics of lesser importance.

Vice President Pence is involved with Latin America, especially the “Northern Triangle” of Central America, but – put simply – Nicaragua isn’t on the White House agenda, unless Ortega should decide to burst into it by force, launching a reckless challenge to lighten the load of “Maduro’s battle against the empire.” In that case, it wouldn’t be difficult for Senator Marco Rubio, who maintains a direct line to Trump (counseled by the former undersecretary Roger Noriega), to connect the president to Nicaragua via the 140 characters of a tweet and set in motion the machinery that Juan Cruz directs in the White House.

As long as this short circuit doesn’t happen, Ortega’s regime, with all its corruption and lack of democracy – with the political backing provided by the large business class and the prevailing authoritarian climate of stability – contrasts favorably in matters of security with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and will continue being merely a case under observation. Certainly, the virtue of the “Nica Act” is that it’s put on the international agenda the corruption that’s been well documented by the investigations of the independent press in the country. But while Nicaraguan society doesn’t recognize out loud that the diversion of more than four billion dollars of Venezuelan state foreign aid into private channels that used it for personal businesses and spurious capital projects in the shadow of the political regime represents a crime that should be investigated and punished, we can’t expect any solutions from outside.

The agenda for change, as distant as it may look today, involves bringing to light and connecting the struggle against public and private corruption with the social demands and the fight of the social movements, including the Sandinista sectors.

The agenda for reform that the country needs – employment and anti-poverty measures, quality education, fiscal reform, social security, repeal of the Ortega-Wang canal law (Law #840), salvation of the environment, municipal autonomy, full democratic freedoms, women’s rights, the professionalization of the Army and the Police, separating the State institutions from political party control, and a growth in equality – covers the entire national spectrum: independents, Sandinistas, the opposition, the business community and the social movements.

However, only through pressure and social mobilization, even at the price of the political instability that the authoritarian repression could temporarily provoke, can we achieve a true electoral reform that would open doors to political change and a democratic transition.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D